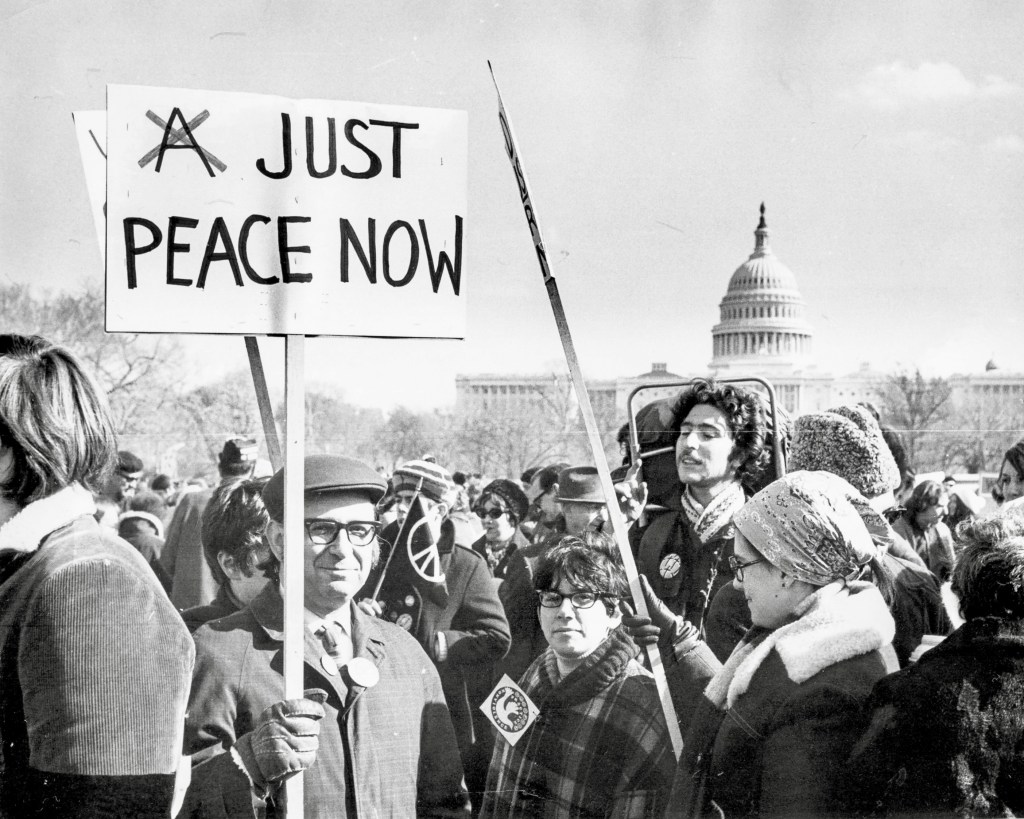

I spent last week in Washington, D.C., in meetings with a group of Israeli and Palestinian peacemakers colleagues and I have accompanied and worked with for nearly a decade. This initiative is convened by the Herbert C. Kelman Institute for Interactive Conflict Transformation in Vienna, Austria. The Kelman Institute was named in honor of one of my main mentors in the field of negotiation and conflict resolution, Herb Kelman, who fled Vienna with his family when he was 11 following Kristallnacht. I was thinking about Herb a lot and missing him last week. Herb died in 2022, just before his 94th birthday. Several of his colleagues and students eulogized him at a memorial service in September 2022. I’ve posted my remarks below, as well as a few photos of Herb. Donna Hicks, Dan Shapiro, and I later offered tributes to Herb as a scholar-practitioner through the seminar on international conflict analysis and resolution named in his honor at the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School. I wanted to post something about Herb here, in part, because I posted a tribute to another of my mentors, Roger Fisher, in 2012 after he passed.

Many of us here today participated in a festschrift for Herb on the Harvard campus about 20 years ago. Reflecting on his career up to that point, Herb said something like, “Others think big. I always have thought small. I want to start thinking bigger.”

As I recall, Herb went on to explain that he had long focused on understanding individuals—our attitudes and actions and how to influence individuals positively. He then applied what he had learned about individual perspective change to dyads and small groups, perhaps most notably through development of the Interactive Problem-Solving approach to conflict resolution and his work on morally blind obedience to authority.

This focus on individuals and small groups always was aimed at broader societal and global change, of course, but now Herb apparently was thinking about possible systemic interventions at a very large scale. He mused about work he might do with the United Nations—in retirement, nonetheless! I don’t know precisely what he might have been thinking then, but I don’t believe he ultimately changed directions in a major way. Herb mostly continued to think and do “small” as he apparently defined it. Like others here, I teach, write, and practice in the conflict resolution field, and I’m constantly in awe of the major impact Herb’s “thinking small” has had on our field and in the world.

As I was preparing my own remarks for that festschrift I had a conversation with Herb in which he said something else that has stuck with me. I had been asked to comment on two very different presentations, one by Shoshana Zubhoff at Harvard Business School, who would be speaking about what she calls organizational narcissism, and the other by Luc Reychler of Catholic University Leuven in Belgium, who would be speaking about the idea of peace architecture. I turned to Herb for suggestions about how to contend with two such diverse topics, particularly since my own work, on religion, conflict, and peace and what I now call negotiating across worldviews, differs so much from theirs. Herb had no suggestions, only general words of encouragement, but he told me in passing how incredibly happy and proud he felt because those he mentored closely were doing such varied things.

And so I submit to you that the close mentoring of so many of us that Herb did over his long career is another way in which Herb focused on the individual and thought and did “small” with huge impact. Herb’s mentees are making major contributions in fields of scholarship and practice as diverse as business, child advocacy, conflict resolution, education, human rights, genocide studies, international relations, law, medicine, peace studies, poverty reduction, psychology, public health, social work—the list goes on and on.

Herb said many other things over the years that will stick with me but let me share just one more. It’s the last thing he said the last time I saw him while he still was able to communicate. Donna and I were visiting about three weeks before Herb passed away, and he was in bad shape. We mostly just sat at Herb’s bedside holding his hand, because his breathing and speech were so labored. As we prepared to leave I asked Herb, “What do you want us to know?” He responded to my question with another question: “What will it take to bring more people to love?” Herb said.

I think that biggest-of-all questions is what animated the “thinking small” work to which Herb devoted his life. I likewise see this universal question propelling the very particular work of so many of his mentees.

And it’s not just us.

I keep coming across Herb’s name, and ideas, and evidence of his influence in unlikely places, like Michael Pollan’s book How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence. (Most of us know about Herb’s little run-in with Richard Alpert (later known as Ram Dass) and Timothy Leary, who he thought should take a more responsible approach to human subject research, shall we say.) I’m a Zen practitioner, so you can imagine how surprised I was to see Herb’s work cited in Robert Wright’s book, Why Buddhism Is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment. Really?! Herb’s work is discussed in a book about Buddhism? Unbelievable.

In Zen, we say our teachers don’t die, they just go into hiding.

Everywhere.

In and through each of us and so many others, Herb is hiding in plain sight—everywhere.